For nearly 100 years, the faculty of Xavier University of Louisiana has upheld the university’s mission of promoting a more just and humane society by educating the next generation of changemakers and seekers of reform. Founded on the vision that all deserved a quality education in a time when racist practices prevent Blacks and other individuals of color from accessing such merited institutions, Xavier continues to be a haven for communities and groups that have historically been marginalized and underserved. As Xavier prepares to celebrate its first century of service, it continues to solidify a powerful legacy of finding the gaps in the pre-collegiate education of its students and filling them through mentorship, rigorous academics, and quality courses. Cirecie Olatunji, Ph.D., director of Xavier’s Center for Equity, Justice, and the Human Spirit, reflects on the need to reach the younger generation before they become Xavierites or first-year students at fellow institutions.

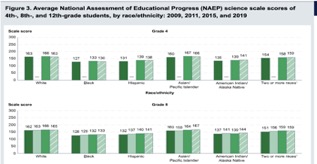

There is a plethora of research on the challenges regarding the underperformance of Black youth [in academics]. A host of scholars from numerous disciplines have investigated this issue, labeling it as the “achievement gap,” with White students and, more recently, Asian American students as the reference groups. While I don’t want to focus on the lack of success, I do want to review their performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests. These are important indicators because they are used nationally as opposed to the assessment tools created by individual states, such as the LEAP (Louisiana Educational Assessment Program) tests. However, it’s difficult to compare apples to oranges as we view student performance from state to state. The NAEP scores give us a sense of what’s happening nationally for children in general, but let’s look at what’s going on for Black children.

The NAEP is administered at the fourth, eighth, and 12th grade levels. Let’s start with fourth grade. From 2011 through 2022, the average NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) reading scores for Asian and White 4th-grade students were higher than those of their peers of other racial/ethnic groups. In addition, the achievement gaps between Asian students and students of other groups generally grew larger over time. In 2022, the average NAEP mathematics score for 4th graders was lowest for Black students (217) in 2022. In general, the achievement gap widened between White/Asian students and Black/Latino students between 2019 and 2022.

To contextualize the most recent test scores, some of the low achievement may be due to the pandemic. Black and Brown children, who are disproportionately represented in low-income families, lost a lot of academic gains during the worst part of the COVID-19 pandemic. That could be one of the reasons why we see that gap widening, and that’s true for fourth, eighth, and 12th-graders.

Similar to grades 4 and 8, the average NAEP science score at grade 12 in 2019 was lowest for Black students compared to peers of other ethnic/racial groups. In 2019, however, the gap in NAEP science scores between White students and students of color has decreased.

|

I do want to just make one caveat when we talk about the achievement gap. Let’s put that term in quotes because students in the U.S. are not doing that well globally compared to other highly developed countries. Thus, I’m not sure if we should regularly compare them to the nation’s norm.

What causes this persistent underachievement? When we look at the extant literature, there is a plethora of research on parent involvement and Black academic achievement. This research often suggests that if Black parents were more involved in their children’s schooling and academic performance, the students would likely perform better academically, and then educators could do their job. We have a lot of research blaming parents as the number one cause of Black children’s underachievement.

Despite the prevalence of parenting programs at under-resourced schools, where Black children are disproportionately represented, research studies on parent involvement rarely acknowledge parenting as a culturally informed concept. In other words, does parenting mean the same thing across various cultures? Do we have the same goals of how a well-developed child should look and behave? The indicators are culturally bound.

Therefore, when we look at parent involvement research, it is really focusing on a particular set of values that may not include the values of many Black families. We need to incorporate the cultural worldviews and values of Black families. For this reason, I developed an instrument, the Parent Proficiencies Questionnaire (PPQ), for parents of Black children to assess parenting within the context of culture.

The second area of interest is self-esteem and Black academic achievement. These studies typically suggest that the reason why Black children are not achieving is because they have low self-esteem. For that, I ask, “What might cause low self-esteem for a whole population of students?” One causal element that is historical in nature is structural racism. I don’t mean interpersonal racism wherein a particular teacher might be consciously (or inadvertently) racist in interactions with Black students. Current educational research suggests that the educational system's structure is culturally assaultive for Black youth. Culturally assaultive classrooms, curricula, assessments, instructional practices, and expectations have been shown to place Black youth at risk.

The third area of research that focuses on Black student achievement is peer support programs, suggesting that Black children are combative and conflictual with each other and do not have sufficient engagement skills to manage their emotions. These studies imply that Black youth don’t have positive peer relationships and that Black youth are disproportionately involved in substance abuse issues, alcohol issues, violence, and so on. But is this the whole story?

When I taught graduate-level research courses, I emphasized the need for my students to think critically when reviewing research studies. We need to think critically about what is offered whenever we seek solutions. We need to consider what is being said and what is not being said. Looking deeper, we can find research about peer support programs that offers a counternarrative. These studies have findings that assert that Black children do work well with each other, provide support, demonstrate moral conscience, and can make decisions about their peer group.

Finally, millions of dollars are currently poured into trauma-informed care training for educators. Unfortunately, trauma-informed care training does not get to the heart of the matter without a focus on culture. Because when we go back to looking at those scores, the parent engagement, self-esteem, peer support, and trauma-informed care interventions have not significantly changed those scores. If these programs are not working, we need to seek evidence-based interventions that are working.

There are examples where teachers, principals, and whole school districts have had success. However, these successes have not been applied nationally to change the trajectory for Black students. To see this constant lack of change, I often wonder if educators (and parents) think underachievement is intrinsic to Black people. This might explain the lack of a sense of urgency to address persistent and historical underachievement among Black students.

What is missing from the interventions being promoted to address academic underachievement among Black youth is an understanding of the structural issues that require countermeasures systemwide and the microsystemic issues that can be addressed interpersonally. We need to understand the environmental contextual issues, such as the policies. We need to work with teachers using comprehensive approaches over extensive periods of time.

Scholars need to develop relationships with school personnel and community members over time. Researchers need to embed themselves in schools to decolonize their training and then seek to erode the deficit thinking reflected in educational practices.

Finally, everyone needs to engage in the research to seek solutions, whether we are community service personnel, parents, school educators, or mental health providers. We need to engage in inquiry. We need to be actively involved in developing solutions. The time is now!

Cirecie Olatunji, Ph.D.

Director, Center for Equity, Justice, and the Human Spirit